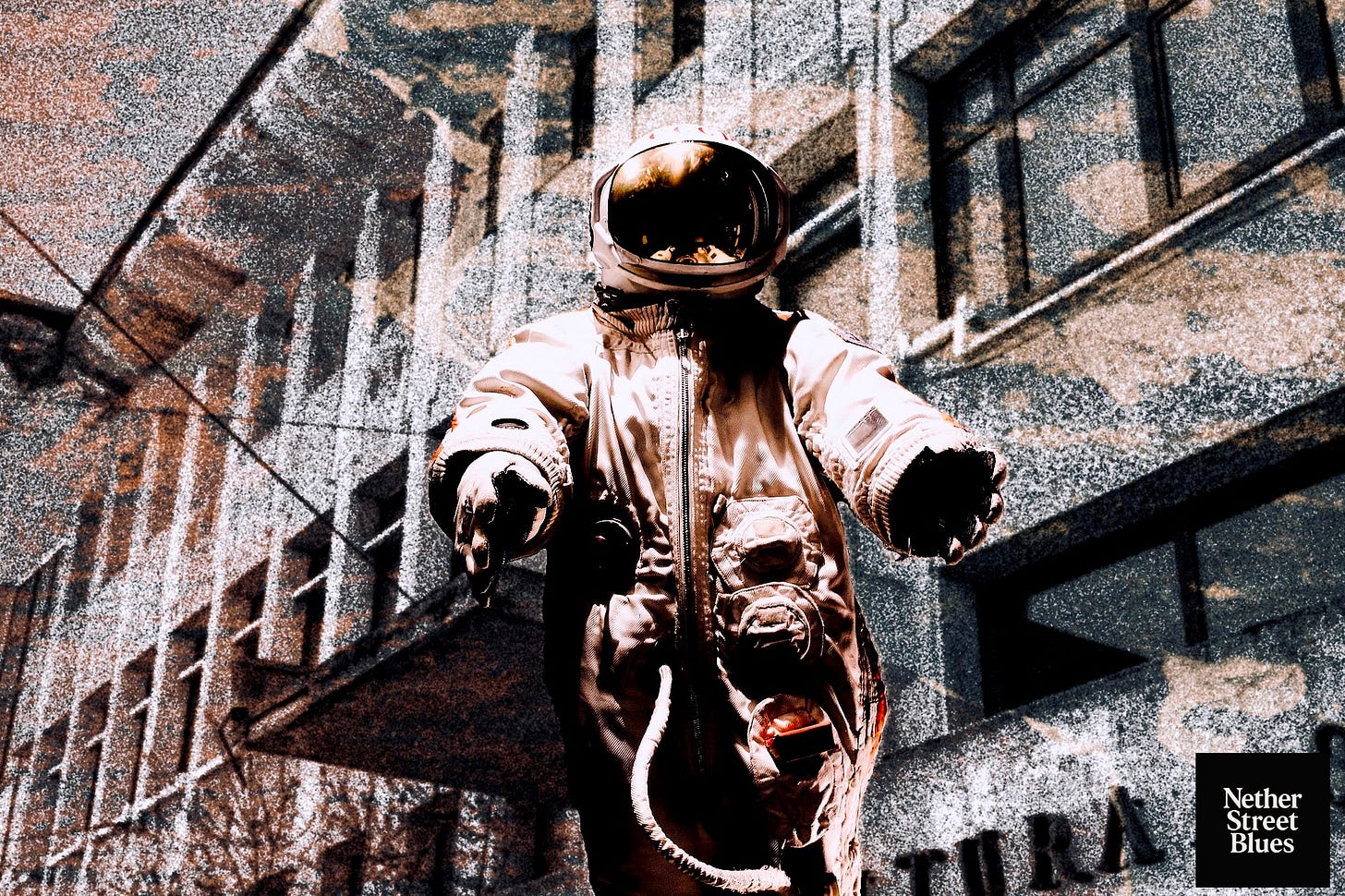

The Cosmonaut, Part 3

"Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one." Albert Einstein

Beloved readers, the wait is over—Mihai Văzduh’s journey through the Nether continues, with a turn none of you saw coming. If you’re just joining us, this is a great place to begin (earlier entries are linked below if curiosity bites).

Let me also leave you with the Sovietwave playlist that shaped this chapter’s mood.

“…the worlds he had walked, each life lived and lost, each self-cast off like a shedding star, drifting from world to world, age to age, moment to moment through the chasms that sunder lives as sleep sunders waking, as birth sunders death…”

“Mihai, please stop. That’s enough for today,” the teacher said, removing her gold-rimmed glasses and rubbing her eyes. She let out a long sigh, the kind Mihai could feel on his neck.

He raised his eyes from the notebook and avoided looking at his classmates. Instead, he stared up at Ceaușescu’s portrait above the blackboard. He bit his lip and focused on the smile. For a moment, he remembered Grandpa’s remark: That used to be a place for an icon.

“Make sure your father comes to the next meeting. I know he’s busy serving the Party and the country, but I need to speak to him. Your mother just won’t do.”

Mihai knew he’d crossed a line. He just didn’t know which one.

So it was to be.

Oh boy.

A quiet giggle rippled through the classroom. But when he looked around, most of the faces were solemn.

Mara—his deskmate, his self-proclaimed secretary, the one who’d asked Ms. Duna to let him read the composition—fidgeted beside him, her guilt obvious. At recess, she apologized to him, but Mihai told her there was nothing to apologize for. She looked at him with her big eyes—Princess Maria Bolkonsky eyes, as Grandpa had called them the first time she came over to their two-bedroom apartment on the eighth floor in the new neighborhood of Pajura.

That memory came and went like a cool breeze through Mihai’s head, which was burning with quiet shame.

The rest of the day passed both slowly and fast, like a faint nightmare of history, math, and shop class.

As stressed as Mihai was that day, his father wasn’t angry with him at all—something that stressed him even more. For Mr. Voicu, the teacher’s call had been a long time coming.

Mihai was already in bed, next to his snoring grandfather, by the time his father returned from school. But he wasn’t sleeping—he was reading under the heavy duvet, using the German flashlight he’d received as a name-day gift last year.

His room was right next to the kitchen. When he heard the apartment door open, he grabbed his night water glass, downed it in one go, and used it as a listening device, pressing it to the teal wall and leaving a round stain.

His mother was bubbly, trying to preemptively defend her little boy by performing the role of model wife. His father replied in grunts and mumbles.

Later, over supper—after his first shot of țuică and the first of the Pleşcoi sausages—Mr. Voicu finally spoke.

“Well, I can’t blame him. He’s a fine boy,” he said. “He just has this wild imagination. Maybe he gets it from your father.”

“They do spend a lot of time together. But what can I do? He helps him with his homework. And you know how little Mișu is—he’s not like other kids. I’m just glad he has Mara for a friend. And what a good friend—”

“Oh, don’t get me started on that girl. She’s always encouraging these... fantasies.”

“What delusions? They’re kids. Let them dream,” the mother said, refilling his glass with a splash more țuică.

“I don’t know what you want me to do. I’ll talk to our son in the morning. Tell him that kind of stuff isn’t appropriate for school. Maybe get him to write about Dumitru Prunariu—you heard he’s been selected for the Interkosmos space program? A real Romanian in space. And no fascist involvement to boot.”

Mr. Voicu let out a hearty laugh as he downed the glass. He was ready for bed, his eyes drooping. But the smile quickly faded.

He sighed.

“But you know, my dear... I don’t think it’s an intellectually safe environment. Not when a kid hears his grandfather call himself an ancient god. I suppose I should be thankful—it could’ve been worse.

But he’s going to get us in trouble with those stories of his. Did you hear what he said in class? He talked about an alternate universe where the fascists won.

Who writes that kind of stuff?”

He paused, then muttered:

“And things are getting weird. Today we had to arrest a drunk for shouting Long live the king in Hanul Berarilor. Poor soul doesn’t even remember. But Bădescu says he’ll probably do time. It’s not safe, is all I’m saying. I know he’s a kid. But the regime…”

Mihai’s grandfather—Mr. Zaharia, as all the neighbors knew him—used to be Father Zaharia when he lived in Moreni. But that was another life, a life taken by the communist regime, which forced him to betray his spiritual children.

Afterward, the former priest took to drinking and smoking heavily, spending his days reading the forbidden books he still kept hidden in his library. His son-in-law, a Securitate officer, used all his influence to pull him out of that predicament and bring him to live with them in Bucharest.

Mihai’s mother was moderately grateful for this—and she might have been fully grateful, had her father not renounced both the priesthood and his faith.

By the time he arrived in Bucharest, the old man was well-versed in Guénon and Evola, authors he had to leave behind in the Moreni house so as not to offend his benefactor.

That predicament—his fall from grace, his exile into thought—was, to Mr. Zaharia, the greatest blessing he had received from the Sky Father. To his still-religious daughter, it was a tragedy.

Every night and every morning, while the men of the house were asleep, she would prostrate herself in prayer asking only that her father’s soul be saved. She would do this in the living room; the grandfather and grandson shared the small bedroom.

After his parents left the kitchen, Mihai put down the glass and went to the bathroom to pee out the water he’d downed earlier. When he returned, he found his grandfather reading his latest story, The Cosmonaut visits Planet Ephraim, by flashlight.

“Your story is shaping up nicely, my boy,” the old man said. “But your folks won’t appreciate it. Best you keep it to yourself.”

He flicked the flashlight toward the bed to light the way for Mihai to climb in. Then, with a quiet grunt, he shuffled to the window and pulled the drapes aside just enough for them both to peer out into the night.

“See the city, old man,” Grandpa said to Mișu, eyes squinting at the skyline. “Look at it towering over us. We’re living higher now than any of our ancestors ever dreamed.”

He tapped the window glass like it was a map.

“But remember: this was all plain once. Wild and untamed, as far as the eye could see.

And they kidnapped the daughter of a shepherd named Bucur. Brought her here in chains.

Bucur came for her. Came with blood and fire. Saved her. Claimed the land as good. And from that, he built this place: Bucharest.”

“What’s the point of this story, Grandfather?” Mihai asked.

The old man scratched his long beard, then smoothed it thoughtfully.

“What’s the point of any story, Mișule, my boy?”

Mihai ducked his nose under the heavy duvet, then poked it out again to reply,

“That’s not an answer. But I know what you mean, Grandpa. We need to be brave if we want to be remembered.”

The grandfather chuckled and waved his hand in dismissal.

“Or maybe… maybe it’s that we need to believe we’re here now because some of our ancestors were brave then. Maybe there was no Bucur. Maybe Bucharest happened because it was close to everything and to nothing. But that’s not a good story, is it?”

The boy nodded. They smiled at each other in the shadows.

“Do you like his name?” Mihai asked as they were both falling asleep.

“Whose name is that?” asked Mr. Zaharia.

“The Cosmonaut’s, Grandpa…”

“You mean your name?” the old man said faintly.

“He’s Mihai Văzduh. I’m Mihai Voicu, Grandpa…” the boy murmured, lying on his side, their backs pressed together for warmth—a technique Mr. Zaharia had taught him when he moved in.

“If you say so. But we all have a hidden name. One that doesn’t appear in any identity bulletin or report card. One that’s given to us by the Architect-of-All.”

The boy was already drifting into sleep and didn’t try to understand. Still, he asked:

“What’s yours, Grandpa?”

“Zamolxis,” the old man whispered. “But that’s a story for another day.”

Outside, the wind pressed against the window like an old breath. The kind that carries dust, and voices.

Mihai closed his eyes, but somewhere, beneath sleep, he saw his grandfather standing at the mouth of a cave: not old, not young, not smiling.

“The first stories are for comfort,” he said. “The real ones come later. When you’re ready to leave your name behind.”