Author’s Note: Beloved Netherwalkers,

Because this tale is longer than I usually intend to publish electronically, and because I truly care about your tired eyes, I’ve divided it into distinct sections. Please, pause as often as you need, especially now, as the nights grow shorter.

A Letter From Nowhere

I must begin by apologizing for my prolonged absence—and for the silence, which I fear may have been gruesome in its own right. What follows is my best attempt at an explanation. But as you’ll soon see, such a thing borders on the impossible. No matter how I arrange the words, the text fragments, the message unravels into madness.

As you will undoubtedly recall, I departed from London in the summer of 1862, having accepted a post with Barkley-Staniforth & Co. My commission was as chief engineer for constructing the first railway to link Bucharest to Giurgiu.

A terrible city, Bucharest—if one could even call it a city. It is more a happenstance conglomeration of modern façades and wretched slums. From my apartment at Hotel Concordia, I could see the tangle of alleyways near Smârdan Street, where peddlers, prostitutes, and beggars rubbed shoulders with intellectuals, boyars, and the so-called upper crust. I might have been happier when I had the chance to leave that place and venture into the beautiful countryside, if not for the abject poverty and primitivism of the villages, and the moldy inns where we were forced to spend the night.

Civilization & Other Shadows

“But, mon frère, there’s no need to trouble yourself with bandits or outlaws in these parts. The country has grown civilized since the Union,” said my old school chum from Paris—a poet of some renown in this wretched land that now dares to call itself Romania.

The coach had no roof, and the brutal sun pressed heavily above us. The horses of the small troupe of gendarmes escorting us toward Giurgiu were snorting, as if echoing my discomfort beneath the unbearable heat of the southern plains below the Carpathians. The sun had been setting for what felt like an eternity, and my handkerchief was drenched, even after wringing it out more than once.

“We’ve assembled quite the little army, haven’t we?” said Vasile, the poet.

“Well, we’re carrying the payroll for the entire railway company. Even if I were riding from London to Canterbury, I’d have had security,” I replied, careful not to offend my friend. After all, in his lifetime, his country had civilized itself by leaps and bounds. I remembered how, during our school days in Paris, the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia had not yet been united. According to dear old Vasile, independence from the Ottomans was the next step.

“Independence, and then union with Transylvania,” he repeated often during my stay.

But knowing Westminster’s desire to keep the old Ottoman Empire upright, I knew this dream was no more likely than our longing for King Arthur to rise again.

We were still a long way from Giurgiu when dusk finally gave way to night. Yet as we entered a thicket and the air turned cooler, I found myself absorbed in an interesting conversation with Vasile about the future of Europe.

I should have mentioned sooner that this fine man had once been a revolutionary, back in that fateful year of 1848, when the peoples of the continent rose to claim their liberty.

My shirt was still drenched with sweat, yet my muscles shivered. I wrapped myself in one of the blankets we had brought along.

“Quite the chill tonight. Might be the winter wind come early,” said Vasile.

The coachman muttered something to him in their tongue, to which Vasile scoffed and shook his head.

“Progress, mon frère, will come, but not for these primitives. I daresay, once your railway is complete, the villagers who see the train passing through will think the Devil himself is pulling it.”

He chuckled to himself before continuing.

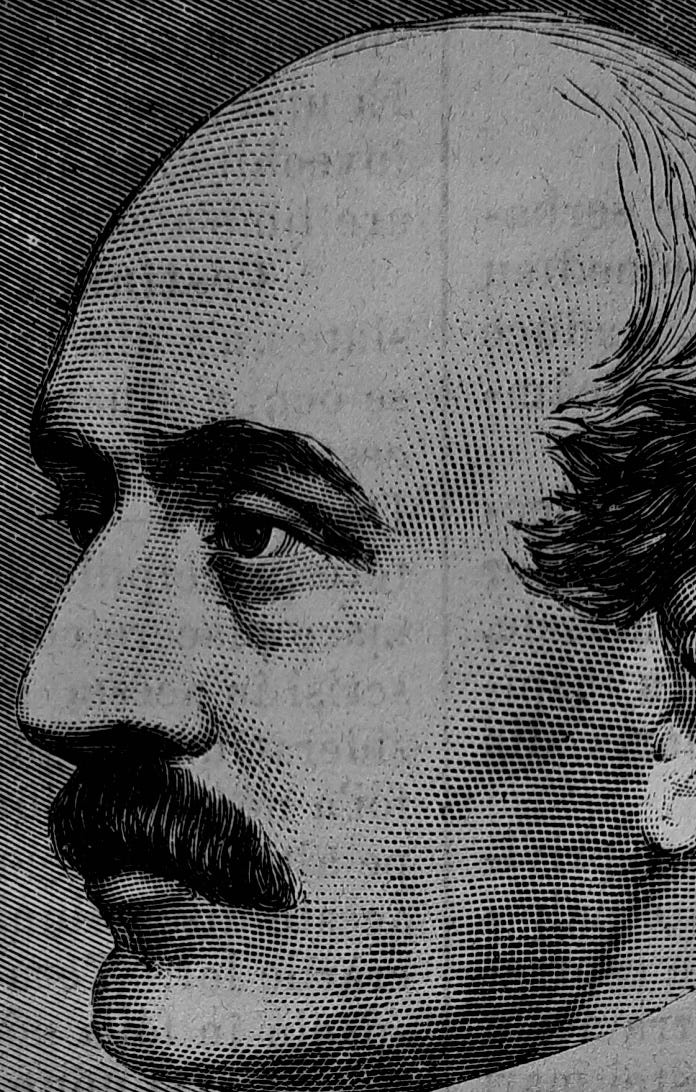

“They say some famous outlaw—a haiduc, as we call him—has been spotted in these parts. A Robin Hood sort, now risen in the minds of our people to something near saintly. No, more than that—Heraclean. His name was Andrii Popa, but he died at the hand of my godfather nearly half a century ago. A bandit, without question. And yet, ask any villager and they’ll tell you he freed would-be slaves from the Ottomans, that he gave all he stole to the poor, that he fought in every revolution we ever dreamed of.”

He smiled faintly.

“On my word of honor, I wouldn’t be surprised if their children one day claim he built your railway.”

The Toll & The Flute

I awoke when the coach came to an abrupt stop. I had fallen asleep listening to Vasile’s diatribe against the ignorance of Romanians and the fantastic tales surrounding that Andrii fellow. Through the dying haze of my dreams, I could hear a flute, almost a melody, but formless, like the wind.

Gleefully, I rose at the sound of horses squealing. Apparently, we had been stopped.

"A toll tax, says the coachman. But there are just eight of them, and we have more than a couple dozen armed men," Vasile assured me, though heavy beads of sweat were forming on his bald head, glistening in the moonlight.

"They are just some good old boys, I say. Surely our men will make them see reason."

But no sooner had Vasile spoken than gunshots cracked from the thicket. Loud gunshots, louder than a cannon.

The bandits, I could not see them; they moved too fast, like ghosts. Only the flash of steel could be discerned. I saw our men felled one by one, and even the outlaw horses seemed to bite and rend at their enemies.

The coachman leapt between the benches in the back, crying out the name of the Almighty.

As quickly as it had begun, the violence gave way to a strange, breathless calm. Only three of us remained, Vasile, the coachman, and I, the gendarmes having either fallen or vanished into the night, leaving us behind with the bandits.

And still that maddening flute played, its melody shapeless and eerie, as if the wind itself had learned to sing in mourning. It came from nowhere and everywhere at once, like a tune carried across centuries, too old to be remembered and too familiar to forget.

The Bastards of Mad Wenches

Oh, if only they were bandits. I saw them crouched over the bodies of the fallen, slurping at the blood that pooled on the dark earth, like beasts at a sacrificial altar.

Then one of them approached, their leader, draped in a heavy fur cape, a weathered shepherd’s cap resting on his head like a crown of derision. In the silver light of the moon, I saw his eyes burning red, not like coals, but like living embers. And his face—ah, his face—was the visage of a skull, worn thin with time, stretched over the memory of a man.

When he drew near, I saw that he had only his right arm, and that it held a long Arabian dagger, the infamous hanger of a haiduc, which he stuck into his wide leather belt, a chimir, worn scabardless.

"Ça ne se peut pas !" Vasile exclaimed.

"But it can, boyar. Oh, it can."

The voice spoke to us, though it did not pass through the air. It came from within, from my own heart.

"Now give us your treasure, and we shall leave you be."

"That I cannot do," I found myself saying. "These are the wages of honest men, the workers I am responsible for. I will not allow myself to be looted without a fight."

"We have no quarrel with you, foreigner. And do not pretend you care for those men you work mercilessly beneath the hard sun, toiling in the dust of the Dry Valley."

Reaching for the revolver tucked away in my riding coat, my hand froze. And the bandit leader laughed.

"You have some bravery in that city heart of yours, foreigner. But there is no need for you to die over coin that is not yours—coin that is insured."

Those red eyes burned a hole straight through me.

"Captain, the sun will rise soon. Let us finish this fool and retreat to the hideout," cried a shrill voice from one of the men now gathering blood and entrails in earthen vessels.

I could hear birds beginning to chirp, their songs weaving into that formless flute, creating a mad symphony, nature itself unhinged.

"Shut your blood-sausage hole, Neferu. You know this is not our way," the captain snapped. "We will not make it far with the night as short as it is."

Then he turned back to me, and I could feel the strange grip he held over my limbs begin to loosen.

"You can try to shoot at us," he said, his voice low and sure, "or you can live, and join us at the Lodge on the Peak of the Ages."

I turned to Vasile, who had frozen in place, his mind agape, a look of sheer terror stilted on his face. Before I could speak to him, I saw the coachman tying two of the dusky steeds to the coach, handing the reins to the leader and the one called Neferu, who had already leapt inside. They smelled of death, smoke, and pine.

"Oh, good boyar, be not afraid. We are but your friends," said hunchbacked Neferu as he helped Vasile sit down, caressing his sweat-soaked bald head with the ragged sleeve of his peasant’s shirt. A gleeful smile spread beneath the dark moustache that barely concealed what were unmistakably the fangs of an ancient sabre, the very kind whose skeleton I had once seen displayed at the Natural History Museum.

The Waxen Road

The road was still dark, though the sky had begun to brighten. We rode in silence for some time, the flute melody trailing behind us like fog. I noticed one of the dark riders carrying it, and for a moment I thought it was truly a flute.

When we reached a crossroads, the leader spat blood onto his clawed fingers and marked my forehead, then those of my companions.

He gave a signal, and the strange melody ceased, for the flute was no instrument, but his left hand, shriveled and mummified, clenched into a brown fist.

Two of the riders dismounted and lit candles. From each flame rose a ribbon of white smoke, and together the smoke formed a road, shining and pale as wax. In its faint light, I saw that the mark drawn on our brows was a crude serpent, biting its own tail.

"Before we ride together on this waxen road, let us know who you are," I said, my voice trembling.

"We are the bastards of mad wenches," Neferu replied. "Our mothers went into the woods on the night of Sumedru and lay with these night-kin of ours. We have tasted death without dying, and now, that is all we taste. Oh, boyar, we live, but there is no life left within us. That is why we need blood. For blood is life. But we cannot stand in the light of the sun; it is too much life, mixed with death."

He was already spurring the horses toward the white road as he spoke.

"That may be," I said. "But who were you, when you were alive?"

"Why do you not ask your friend, foreigner," the leader said. "He bears the mark of my killer."

Vasile made to cross himself, as the Slavs do, but Neferu snapped his riding crop across his arm with a quick flick.

"Boyar, you will not die tonight," he said. "Andrii is honorable, even if we cannot help ourselves from being cruel."

The Lodge

And what can I tell you of that place they call the Lodge on the Peak of Ages? It was like a dream—not a nightmare, no, but a strange nightly vision. Another life, if such a thing could ever be.

Outside, it was bitter cold, for we skirted the very edge of the void, shaded only by a few lush green branches of Yggdrasil. Inside, the lodge was crowded with strange beings, a scene Hieronymus Bosch might have painted, had he ever conceived of an interior.

We, the three of us, were served a soup of ecstasy and fear, followed by lamb dipped in glory, with a small side of longing, while our captors—or dare I say, our hosts—feasted on raw blood sausages, washed down with distilled plasma.

And what can I tell you of those beings? That I saw dinosaurs eating beside Viking raiders, served by barely human fricatrices. That Mongols dined with men made of metal, and ebony elves floated beside clouds that sometimes took the shape of wolves and then of men—the vârcolaci, they were called.

I saw a multitude of snakes devouring one another, and they whispered to me that they were the souls of ambitious courtiers, consultants, and lawyers, the demons tucked deep beneath the folds of conscience.

Our hosts were taciturn, apologizing for their rudeness. They told us that after so many eons, they had exhausted all subjects of conversation, save for The Hunt. Such was the condition of many patrons.

"Still, I must inquire—what is this place?" I asked, in a state that went beyond drunkenness.

"What is any place, foreigner, if not just a point between two journeys?" hissed Neferu. Andrii slapped him lightly on the back of the head.

"It is a place for hunters," Andrii said, nonplussed, as a Londoner might speak about the weather. "But more importantly, it is a place for the Hunt itself."

"And what hunt is that?" Vasile inquired, his voice trembling.

"The Hunt that is at the heart of all hunts. The Hunt that lies in the heart of every man, woman, and child. The hunt that brought us down from the trees, that drove us from the caves, that made us cross the seas. The hunt for man and the hunt for beast. The hunt for one's true life."

The Return

When the night ended, I could not say. But I awoke in the coach beneath a star-scattered winter sky, neatly wrapped in blankets between my friend and the coachman.

We had arrived in a village and were quickly invited to a modest feast of potatoes and pickles in honor of the Christmas fast. Yet they gave us tea and țuică as well, perhaps out of mercy, or memory, or some unspoken understanding.

I noticed a few of the young peasant wenches slipping away from the table in the great house where we were hosted, following the riders who had brought us here. I was so exhausted I must have collapsed on the first bed I found.

In the cold morning, I asked for a strop, a razor, and a mirror before stepping into the yard to smoke my pipe. It was then, as I shaved, that I saw my hair had turned white. The shock was brief, no more than a flicker, and then came only a weak sigh.

As I worked through a two days’ stumble of beard, the village elder approached, saying nothing, rolling a crude cigar from a scrap of notebook paper. I thanked him in my broken Romanian, that cursed language which is neither French nor Italian, but carries a Slavic flavor and a heavy load of Turkish words.

By the time I finished, Vasile had joined us, lighting his pipe with the gleeful smile of a man simply grateful to be alive.

"I tell you, mon frère, I thought I was dead when I saw the spectre of Andrii Popa last night," he said. "He knew who I was. I thought he would surely revenge himself upon me for the deeds of my godfather. Blessed Providence! Indeed a hero, I tell you."

I wanted to ask about the gendarmes, but I stopped myself. Even now, as I put pen to paper, there is still so much I do not know. But like Vasile, I was happy to be alive.

"They took so much," said the village elder, resting on his rough cane before spitting into the dust. "Them boyars and princes sent down by the Sultan, they took all we had to give. And then they took some more."

He shifted his weight and looked out across the frozen yard.

"So it’s good we’ve had these good old boys to look after us in their own wicked ways. It’s nice to receive, is all I’m saying."

"But these are monsters—abominations in the eyes of both God and Man," I said, though my shout came out a whisper.

The old man looked at me from beneath his leathery eyelids and let out a soft sigh that might have been a chuckle.

"They’re curious fellas, ain’t that so? But Andrii and his men have been nothing but kind to me and mine, all my life."

"But what about the honor of these young women?"

The old man shrugged.

"Oh, you good and mighty boyar, we’re too poor for honor around these parts. They take care of those girls, that’s for sure. In all my years, I ain’t seen one grow heavy with child," said the old man, staring into the distance, beyond the hills, the forests, and the sky.

Maybe he was looking at the Lodge on the Peak of the Ages.

I know I am.

Authorial Postscriptum & Acknowledgements

This story could not have existed without the album Mugur de Fluier by Phoenix. I highly recommend the song "Andrii Popa"—a ballad about a legendary haiduc, or hajduk as he might have been known in neighboring lands. I was obsessed with it as a child, and its spirit still haunts these pages.

If you wish to hear the flute I mentioned, I also recommend "Strunga," another song from the same album, which sings of haiducs and the wild, forgotten roads they traveled.

Another necessary element in the making of this story was my literary friend,

, It was on his post, To Be In Vogue, that I left a comment—and there, the seed of this tale was planted. I also highly recommend his story The Dark Has It, which provided me with inspiration midway through the writing of this piece.I must also thank another literary comrade,

, for our discussions on creativity, which gave me the framework and momentum to complete this project with such speed and lack of effort. I highly recommend his One of the Chosen.

I’m still in the middle of reading but I love how visual it all is! I think u did a good job with the scenes🥰

Great work, Stefan! Glad to have finally read it, felt like a classic vampyre story from the very beginning 💚